The industry continues to split discussions about technology and business practice, but this discourse needs to change, says DPP managing director Mark Harrison.

The business of making media has never been in greater turmoil. Huge amounts of content are being produced, but not necessarily making money. Mergers and acquisitions are commonplace. And the change-overhead of adapting to new modes of supply is enormous.

Anyone who runs a membership organisation such as the DPP is acutely aware of just how focused every company now is on its bottom line. Budgets are tight. Resources are constrained. Everyone needs to demonstrate a return on investment for every cent they spend.

Read more: DPP delivers documents for IMF deployment

But this febrile commercial environment conceals an odd paradox: when the media industry gathers to talk about how it manufactures its core product – audio-visual content – it is reluctant to talk business. There are any number of technology conversations about IP, the cloud, AI and so on; but few that specifically explore how those technologies improve efficiency, and fewer still how they drive revenue.

The absence of such conversations isn’t simply the failing of those who programme industry events. I’ve asked several industry leaders why we’ll rarely find CFOs and CTOs on the same platform, and their answer is simple. The lack of public dialogue between business and technical leaders reflects what happens in private. Despite the fact that many CTO roles are now held by leaders with business and operations experience, rather than by engineers, it is still rare to find close working between the technical and commercial realms.

"Content got commoditised”

So how did this strange state of affairs come about? Does it matter? And if it does, what’s to be done about it?

Let’s look first at the separation between technology and business. It probably dates from the time when the media industry was supply led. Those were the days when broadcasters supplied programmes when they were ready, from a tech stack of the broadcaster’s choosing. That content, and all the processes that got it from idea to living room, were paid for by a buoyant advertising market or a guaranteed levy, depending on whether the model was commercial or public service. As anyone who has ever attempted business analysis in media will confirm, no broadcaster had any idea of the true cost of creating, managing and delivering an individual programme.

And then, of course, on 23 April 2005, a man posted a video of himself visiting a zoo on a thing called YouTube, and the world changed. New tech enabled whole new media businesses – led not just by media companies but by tech companies too – and empowered consumers to shift the content model from supply to demand.

Suddenly content became global and ubiquitous. It could also now be seen not just as something to attract revenue at the moment of publication, but also as inventory to be maintained and managed in order to extend value, and fuel new business lines. In short, content got commoditised.

Surely this was the moment when technology and commercial executives finally fell into a warm embrace? Not exactly – at least not in the established media community. Business and tech have always been natural bedfellows in Silicon Valley. But among media executives with more traditional hinterland, the transition from a world of linear programmes to one of non-linear assets was seen as something to fear rather than celebrate. And while the CFO tried to make sense of the change, their CTO colleague kept demanding unfathomable amounts of money to fund it.

So while the relationship between the consumer and media had been transformed, the one between business and technology largely had not.

Which invites our second question, does it matter? It’s hard to know for sure. There’s no common understanding of what efficiency and agility are and how they can be measured. With the supplier community going through as much change as their customers, there is little understanding of best practice. Local circumstances and differing stages of evolution, meanwhile, make it almost impossible to compare one media business directly with another.

But common sense suggests it has to matter. The fact is that – among the mayhem – some media businesses are combining commercial and technical opportunities to transform at a remarkable rate. We could be about to experience a kind of accelerated Darwinism in which winners emerge before the losers even had time to spot their coming extinction.

Finally then, what’s to be done about it?

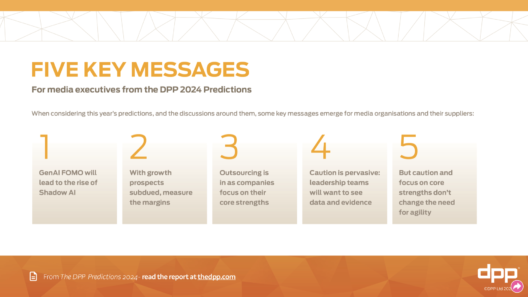

We all have an obligation, in my view, to change the discourse. When the DPP, supported by Imagen, published its predictions for 2019, the themes were overwhelmingly business focused: partnership, transformation in media economics, direct to consumer offerings. Just try applying the question ‘what role could technology play in delivering these business priorities?’ Doesn’t that question place the potential of technology in a whole new light?

This article originally appeared on IBC365.